|

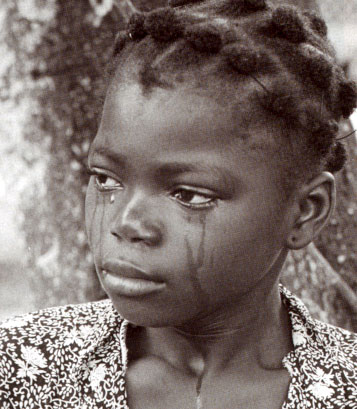

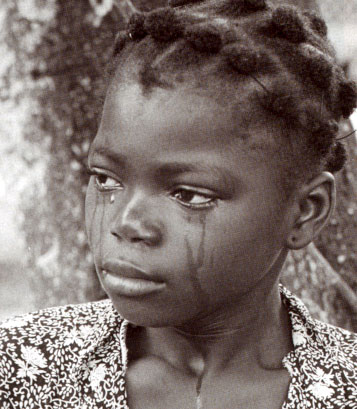

Pictured right Aminata, 11, was enslaved in Gabon. She escaped. She is weeping because she is confused at the idea of being able to eat as much as she wanted. In WEST AFRICA, an alleged slave ship snafu reflects the trauma of an ongoing business of marketing children as forced labour. Africa

has the highest rate of child labour in the world: 41% of 5 to 14 year

olds work. Many children simply help on the family farm or look after

younger siblings. But some are bought or taken from their parents and

forced to work. Most child slaves come from the poorest countries, such

as Benin, Burkina, Faso or Mali, where up to 70% of the people live

on less than £1 a day. "These people are in areas where there

are no options for children, no schools and no jobs," says Beth

Herzfeld, spokeswoman for Anti-Slavery International, a London based

advocacy group. "They don't have the belief that they can build

a future for their families." |

|

| But, "with fabric of the extended family breaking down, things have become distorted," says Lisa Kurbiel, a child protection officer with UNICEF. What was a custom has become an organised trade, with children being taken as far away as South Africa and the Middle East. Closer to home they end up in such places as t6he labour depot in central Abidjan, which offers young girls - most of them from villages in the North of the country - as servants for a few dollars a day. |